Small Data is Beautiful: A Case for Connected Applications

Think about getting the persistence back-end of your next web app right ... sharding, replication, mapping, partitioning, consistency, latency, indices, durability, atomicity, isolation ... any terms familiar?

Familar maybe, but certainly not pleasant.

Modern database systems (e.g. RDMBS/Object DB/Graph DB) are easily one of the most complex aspects of application deployments. This, to a certain degree, is unavoidable given the many intrinsic complexities in working with large quantities of data. However, complexity in designing the persistence back-end of an application is seldom desirable. Storing and retrieving data, after all, is rarely at the heart of the unique business value a system provides.

I propose that many current challenges in working with data could be addressed, not necessarily by the next fancy technology, but by changing the way we think about data. In many current approaches, there is a tendency to make data bigger: building larger systems to hold more data in the spirit of economies of scale and data integration. I argue that we should rather strive to make data smaller: building small, tightly interconnected database systems to hold less data but provide more agility.

I first list a number of problems commonly encountered in using contemporary database systems. I then provide a definition for 'small data' and discuss a number of advantages small data can bring to the development of distributed and evolving applications. Lastly, I synthesize the discussions in this article into the simple PACT Test, which can be used to assess the 'small data readiness' of existing and planned applications.

Contemporary Problems

While there are arguably many important problems in dealing with database systems, I will limit the discussion here on three important key problems:

- Database systems are usually heavy-weight components of applications and are not easily portable.

- Database systems are often difficult to change during development and after deployment.

- Database systems tend to be monolithic and do not easily enable the integration of data on third party systems.

I will discuss each of these problems in the following.

Problem 1: Heavy Cargo

Database systems tend to be feature-rich. The range of features commonly supported includes: full support for an SQL standard, data serialization, index creation, data backup and data replication. These features, while without question very useful, also come at a cost.

First, while databases might offer simple and easy interfaces, these often reduce the complexity on the surface, trading local simplifications against increased global complexity. For instance, it is often non-trivial to estimate the performance of SQL queries (which in themselves are relatively simple but embedded in the global complexity of the database solution). This problem is highlighted when using further abstraction layers such as an ORM framework.

Second, many databases are not easy to deploy. For instance, the Oracle Database 11g Quick Installation Guide is for Linux x86 is 26 pages long. There are, of course, a number of embedded and very portable databases but these are often used mainly for testing with another, more heavyweight database being deployed for production systems.

In summary, database systems are often complex and heavy components of applications. They often make the tasks of testing, deploying, and redeploying applications on different platforms more difficult.

Problem 2: Resistance to Change

Many current database systems are using some form of schema to assure integrity and structure of the data they manage. In case of relational database systems, for instance, the data stored in any table is accompanied by a schema defining the valid fields and field types. Other flavors of database systems rely on schemas as well: many object databases, for instance, require class definitions for all stored objects.

The structure imposed by schemas is a key strength of many databases systems. Indeed, it is the rigidity of schemas, which helps to make data stable, robust and reliable over prolonged time periods. However, in cases when data needs to be agile and adapt to changing requirements at a rapid pace, rigid schemas are seldom of great help.

In general, it is often not easy to change the structure of data stored in a database, change the way the data is indexed or migrate data from one environment to another. This complicates both the development process as well as maintenance and modification of already deployed systems.

Problem 3: The Great Wall

Many database systems tend to enforce logical spaces into which data is grouped. It is generally difficult to integrate data, which does reside in more than one logical space. In particular, it is difficult to establish logical and/or semantic connections between data from different logical spaces.

Relational databases systems, for instance, often use the logical spaces of tables and databases. It is relatively easy to link data between tables within a databases (through foreign keys) but is significantly more difficult to link data in tables, which belong to different databases or even different database servers.

Many NoSQL solutions such as key-value stores maintain few native mechanism to establish connections between different pieces of data. Graph databases, in contrast, are pointedly focused on connecting data in form of nodes in complex networks. However, many graph databases still maintain logical spaces into which nodes are grouped. For instance, often nodes are identified by a form of proprietary node id unique to the server or server cluster of the graph databases. This uniqueness makes it difficult to link nodes stored in one server with nodes stored on another server.

In summary, most contemporary database systems organize data into logical spaces (e.g. database instances), which make it difficult to link data residing within these spaces with data residing in other logical spaces (of the same database system or other database systems).

Proposing Small Data

Although the problems discussed in the previous section describe a number of undesirable consequences of working with database systems today, they are in no way valid as critique on the merit of current technological solutions. Indeed, I believe we have many awesome database technologies, beginning with the maturity of the free MySql, to various great graph databases, object databases and key value stores.

The described problems are less a consequence of insufficient implementations but rather they are the consequence of how data is usually conceptualized. I would argue that, even before the advent of the term big data, discussions of data more often leaned towards making data 'bigger' rather than 'smaller'.

For instance, the article marking the beginning of the age of relational database systems, "A relational model of data for large shared data banks" by E. F. Codd, has at its heart the idea that users access one centralized system, containing all required data in a cohesive and integrated fashion.

While a centralized and monolithic approach has significant advantages in terms of assuring integrity, manageability and performance, today's distributed environments have requirements, which are in conflict with this approach:

- Data needs to be 'open' in that it needs to be accessible by third party systems as well as that it has implicit dependencies to data on third party systems.

- Data and its structure need to be adaptable to react to rapidly changing requirements.

- Data needs to be portable to be available directly on the various devices users use.

I propose that designing data as small data poses various advantages in designing contemporary systems. Below, I first give a brief definition of small data and then describe a number of advantages of small data.

Definition of Small Data

Small data, although given significantly less attention than big data, has recently been discussed in a number of places. Steve Coast defines small data as data, which is manageable using a single spreadsheet. Dany Ayers discusses small data as the interconnected data provided on small websites (in contrast to big web pages such as Wikipedia). Brian Proffitt and Christopher Carfi describe small data in terms of personal data, which can be attributed to a single individual.

Since there appears to be no general agreement on a definition for small data, I will use the following definition of small data for the purpose of this article:

Small data is interconnectable and portable data which can be stored, managed, and processed independently on all components of a distributed system.

This definition of small data has two main components: (1) the requirement of portability and (2) the requirement of interconnectability. Small data should be portable in that there are no conceptual, logical or physical constraints to store, represent and manipulate this data on all important components of a distributed system. Moreover, it should be possible to move parts of the data from one application component to another. Small data should be interconnectable in that pieces of data (e.g. a value, a record ...) can be connected with other pieces of data, regardless of whether they are stored on the same component/devices of the system or on different components/devices.

To give an example: in a traditional system, a central database would usually contain all user details (first name, last name, email ...). If a new user registers using a web application, usually the information containing the user details will be submitted to an application server, which will in turn send messages to a database server. The database server will then ultimately add the user details to the central user details database.

A small data system, in contrast, would require every device involved in an application to be able to store, manage and process the involved data independently. The web application (running in a web browser) through which the new user registers should be able to interact with the user details record resulting from the transaction directly.

Adhering to the requirement of interconnectability, the small data system will further enable to establish logical and/or semantic connections between the user details information held locally by the web browser and other, possibly remote, components of the application. For instance, it would be sensible to connect the newly created user details with a central repository of all registered users.

Moreover, the requirement of portability suggests that any data processed by the application should be portable from one application component to another. The user details created by the web client, for instance, should be transported at some point to a central repository containing all registered users. Since the web client likely requires data from other components of the application as well, data will need to be transported in two-ways, most sensibly as automated synchronization.

Advantages of Small Data

While organizing data as small data doubtlessly poses its own engineering challenges, it provides a number of advantages in building distributed applications. I will describe four key advantages in the following: Proximity, Agility, Connectability and Testability.

Proximity

Latency is a major problem in designing distributed systems. Often, an operation performed on the user interface needs to go through several system layers, each with its own latency costs. This is in many cases unavoidable in traditional systems, since databases are often too heavy-weight to run on all involved systems (see Problem 1 above).

Small data, by definition, requires sufficient mechanisms on every device partaking in the system to manipulate and manage data. In consequence, the data is 'closer' to where it is needed and manipulated.

For instance, let’s assume a user registers and would like to view the user details straight after having completed the registration. In a traditional application such as described in the previous section, a significant number of calls must be made between the various systems involved (please note, these steps could of course be reduced using some form of intelligent caching.)

In a small data application, the user details data will be available locally for the application running on the user's browser. Consequently, latency to perform the two operations of registration and show user details can be dramatically reduced.

Agility

The more complex applications become, the more difficult they become to maintain and change. Data stored in databases is often particularly difficult to bend to new requirements (see Problem 2 above).

Small data, as a consequence of its definition, is more open to change than traditional big data and monolithic data repositories. Imposing global rules and constraints for data involved in a small data application would run contrary to the requirement that every device should be enabled to manage the data it requires independently of other components.

For instance, let’s assume the user registration systems described above would have to be changed in two ways: (1) the web application should issue a warning to the user, if there was no user activity for more than 10 minutes and (2) the application server should keep track of user logins and generate a monthly report of logins per day for the service provided.

In a traditional application, there are essentially two ways to accommodate these changed requirements: First, new data stores could be added to the system as shown below.

Alternatively and more in line with ideals of integrated data, the data in the original data store could be extended to hold the additional required information.

In a small data application, the existing data could be amended at the local data store where it is required (see below). The amended data may or may not be synchronized with the other involved systems. In difference to the first traditional approach, no new data stores need to be introduced to the application. In difference to the second traditional approach, no global and potentially risky data changes are made to the system, which are globally visible and possibly affecting all involved application components.

Connectability

It is often difficult to establish connections between data residing on different systems, preventing truly 'smart' and connected applications. In traditional systems, this is often caused by the physical, conceptual and logical 'walls' around logical spaces in current database systems (see Problem 3 above).

Small data by definition is divided into a large number of independent pieces. Each of these individual pieces provides the opportunity to establish connections with other pieces of data. Data in a small data application further needs to be portable, in that parts of data can be transferred from one system to another.

This portability is an important factor in the connectability of data. To give an example, if a third party system interfaces with the application discussed in the previous sections, it might need a way to identify users in this application. A user id, for instance, might be employed to reference a user record from original application.

The sharing of a user id does not really establish a connection between the involved database systems. In consequence, plenty of custom logic would need to be implemented to assure the integrity of the loose connection between the data pieces in original application and third party system.

It is usually not an option to give a third party system access to the database system of a traditional application as database systems organize their data in 'big chunks', for instance not allowing to grant authorization only for one particular user record.

A small data application, in contrast, should make it easier to allow access to its data to a third party application. In particular, since individual components of the small data application should be enabled to manage their data independent from other components, it should be easier to add a third party system as another 'component' of this system without compromising its integrity.

Testability

Application logic, which depends on data and database features, is often difficult to test. Partly, these difficulties arise from the heavy-weight nature of many databases (see Problem 1) and the difficulty to evolve database schemas in quick iterations (see Problem 2).

Small data systems by their nature are easier to test, since the data is required to be locally available and managed by the component, which works with the data. This also enables testing of the component (including its 'real' data) in isolation from other components of the system.

In a traditional applications, there are often two options to test application logic, which depend on (persisted) data: First, an isolated 'unit' test can be defined for the specific component under test using some form of mock data. This mock data is usually not provided using the database system used in the application. Second, an integration test can be developed, which tests mainly a feature of one component, but which assures the availability of a wide range of system components. Integration tests often use a similar (if not the same) database system as the one used in production (for instance an in-memory database).

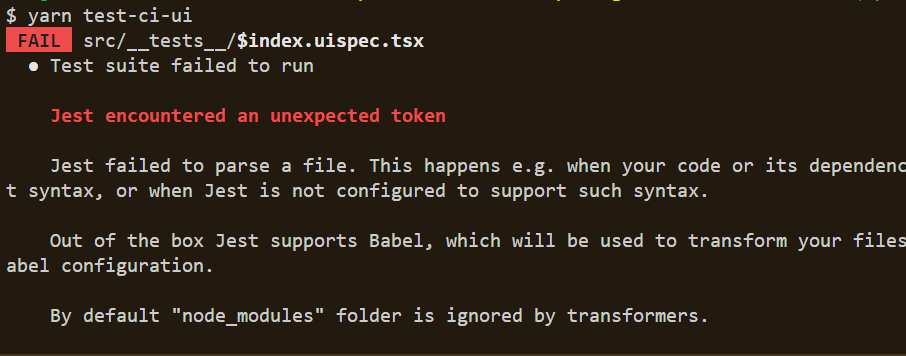

In a small data application, in contrast, isolated test cases can be written against the same database system used in production (since it is a small database system which is portable and can be independently managed by the application components).

PACT Test

Although the term small data is not frequently employed when talking about applications, the advantages described in the previous section might well be realized by existing solutions. Based on the four key advantages of small data systems, proximity, agility, connectability and testability, the PACT test can help to determine the 'small data readiness' of any existing or planned application or application platform.

P: Proximity

- Does the platform enable modules to define, create and manage persisted data independently?

- Does the platform enable modules to query and manipulate persisted data independently?

A: Agility

- Does the platfom enable to change module-specific data without directly or indirectly affecting module-external data?

- Does the platfom enable to change the structure of module-specific data without directly or indirectly affecting the structure of module-external data?

C: Connectability

- Does the platform enable the establishment of semantic connections between pieces of persisted data in fine granularity?

- Does the platform enable the establishment of semantic connections between pieces of persisted data managed by different modules?

T: Testability

- Does the platform enable to test module logic interwoven with persisted data in isolation of other modules?

Limitations & Conclusions

Some questions are not easy to answer: for instance: "Which is better: object-oriented programming languages or functional programming languages?". As interesting as this question might be, it is very difficult to arrive at a conclusive and constructive answer. General approaches and design paradigms are difficult to assess using single-dimensional ordinal systems of better or worse. Is striving towards 'small data' better than striving towards 'big data'? Ultimately, I don't know.

I have listed a number of potential advantages of striving towards making data smaller: these are increased proximity, agility, connectability and testability (PACT) of data-dependent components of an application. However, there are also trade-offs in pursuing small data:

First, building monolithic, integrated systems generally is simpler than building a system of distributed components. Consequently, dividing data into a number of independently managed chunks will result in systems, which are probably more difficult to build than systems with one monolithic data repository. Second, there is a large pool of experience available for big data systems. For instance, we can find specialists who help to stop that one poor performing query from dragging down the system.

I nonetheless believe that there are use cases in which 'small data' can be an attractive choice. These are, unsurprisingly, small systems, which can live without the heavy baggage of a sophisticated data management system, or quickly evolving systems with many independent or semi-independent parts, which would be constrained by having to agree continuously on a common data standard. Also, as the result of my research, I would expect that small data systems could be more successful in supporting knowledge-intensive and unstructured work.

Data needs less complexity. We are spending too much time on managing our database systems; time better spent in delivering new features of business value. Small data following the definition provided here is one possible way of simplifying data with its own advantages and trade-offs. I will be happy to hear your thoughts and opinions.

Please share :)

Provided under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License